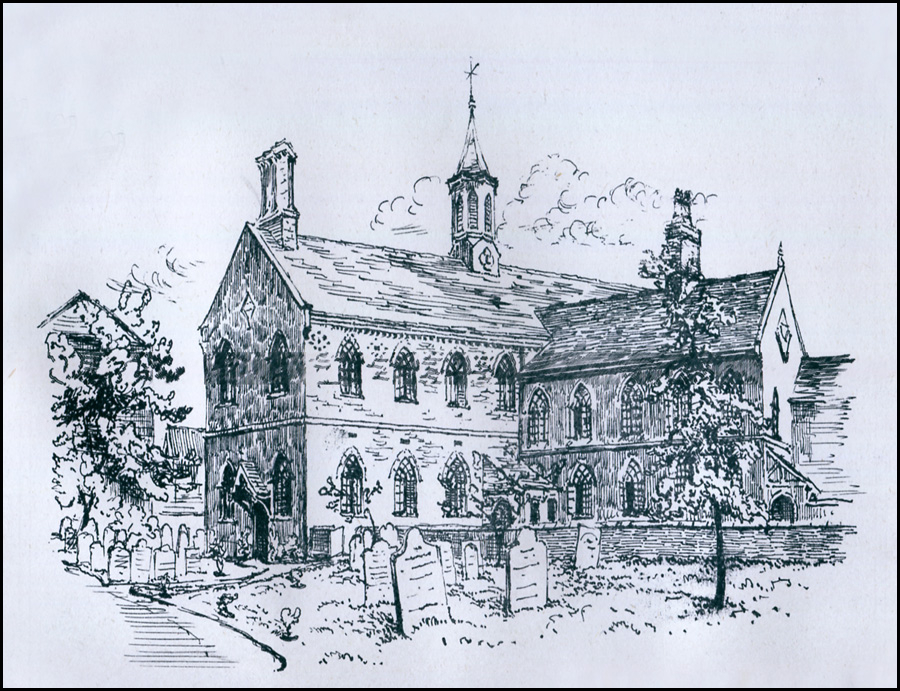

Leicester’s Unitarian Chapel, known historically as ‘The Great Meeting’ – was built in 1708. It is the oldest complete brick building in Leicester and one of the most important historic buildings to survive in the city. The roof is a fine and intact example of early 18th century oak vernacular carpentry and has a unique and ingenious structure which suspends an octagonal plaster ceiling.

The congregation was founded around 1672, following King Charles II’s Declaration of Indulgence which allowed nonconformist ministers the freedom to preach under license. For the next 36 years the nonconformists met in a variety of cramped and unsuitable buildings, including one in what is now called Infirmary Square. Soon after the Toleration Act (1689) which allowed dissenters to construct their own places of worship, the chapel itself was constructed in 1708.

It was designed to meet the needs of two religious groups, the Congregationalists and the Presbyterians, who jointly purchased the present site, originally an orchard beside the Butt Close. The Cherry Tree pub, to this day next door to the chapel, is so named because the orchard contained cherry trees.

The congregation was the most important and influential in Leicester during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and members made a significant contribution to the political, economic, and cultural life of the town out of all proportion to their size or numbers.

William Gardiner was a renowned composer and choirmaster who is credited with introducing Beethoven to this country. Gertrude Von Petzold was chosen as minister at our Narborough Road chapel in 1904 and was the first female minister of any denomination in England. Members of the congregation were active in many progressive causes including municipal reform, anti slavery, votes for women and universal educational.

In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries its members played a leading part in the development of the Leicester hosiery trade. As the economy grew they made a similar contribution to the establishment of mechanised worsted spinning and banking in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

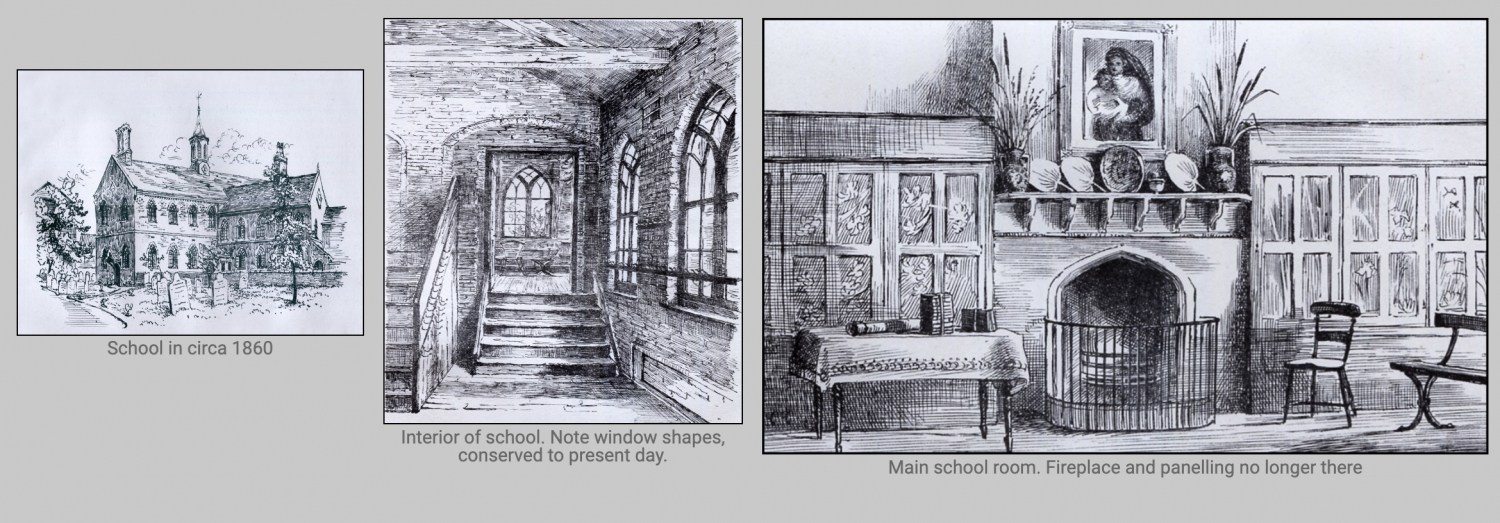

The congregation supported a charity school from the early eighteenth century, clothing 20 boys (in leather breeches) and 20 girls, teaching them to read and write. Children were vaccinated against smallpox and an invoice was submitted in 1750 for ‘washing the children’. In 1813 the congregation built a new school-building (adjoining the Cherry Tree pub), which was enlarged in 1848. Threatened with the loss of the government education grant unless they reduced the overcrowding, the congregation then

built a new range of schoolrooms sufficient to accommodate 1000 children at the cost of £1800; the cost raised entirely from the members. Originally only the basics of reading and writing were taught but by 1860 the curriculum had expanded to include Reading, Writing, Grammar, Geography, Scripture and History, Arithmetic, Vocal Music, and Drawing. In addition, the boys were taught Algebra, Geometry, French, and Drill, and the girls Needlework.Public examinations in the mid 19th century proved that the standards were high.

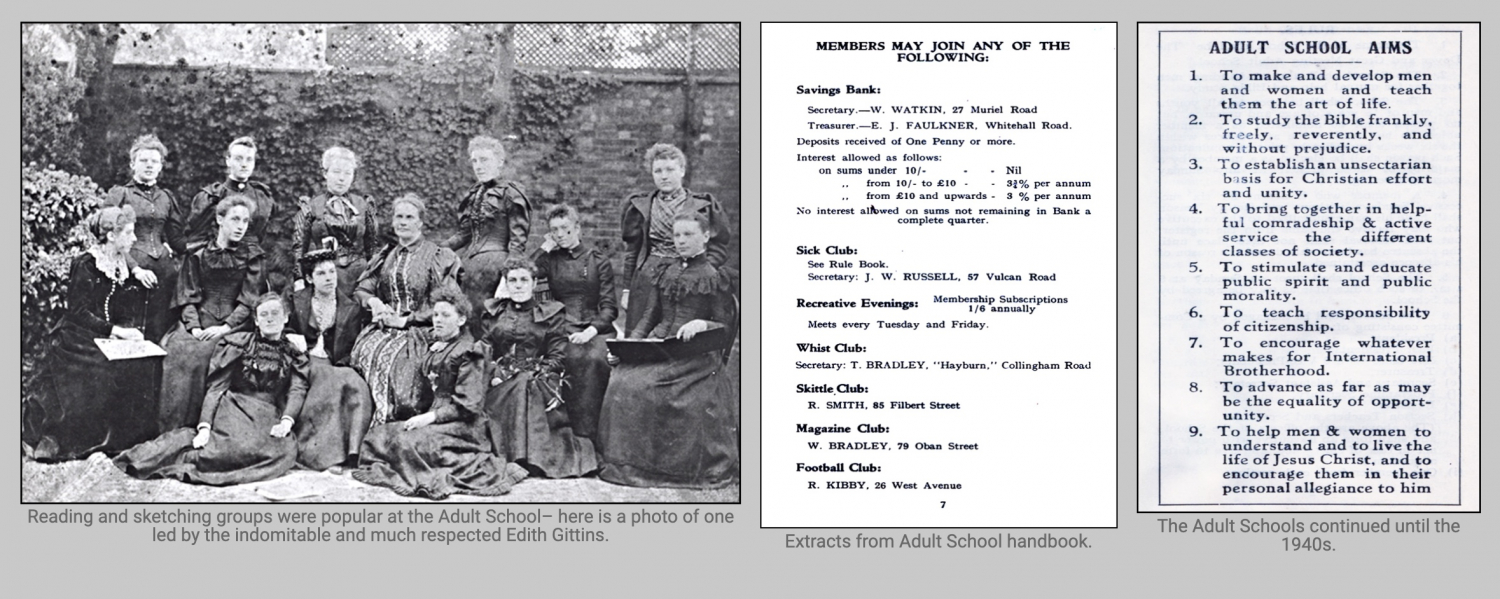

The Great Meeting Day School was closed in 1872 after the passing of the Education Act, but the rooms continued to be used for the Sunday School, for the Adult Schools (motto: ‘Sirs ye are all Brethren, bear ye one anothers burdens’) and were rented out to the ‘Board School’. Interestingly, the stated object of the education was not to make the children specifically Unitarian ‘but to make them good, happy and useful men and women.’

Joseph Dare (1800-1883) was employed by Great Meeting Chapel to run the Leicester Domestic Mission from its inception in 1847 until his retirement in 1876. He was a Unitarian from Hinkley; a teacher, accountant and enthusiastic voluntary worker.

Like elsewhere in England the Domestic Mission aimed to provide social and practical help to the poor coupled with encouragement to lead a more religiously observant life, which in theory was to lead to self-reliance and moral rectitude. In mid 19th century Leicester there was a rapid increase in the working-class population due to industrialisation.

Great Meeting Chapel became surrounded by many poorly built slum dwellings (the notorious ‘courts’). Conditions were dire, with overcrowding, non-existent sanitation, disease, appalling rates of infant mortality, abject poverty and illiteracy. Low wages, insecure employment, child labour, filthy lodging houses and intermittent shortages created the conditions for alcoholism, domestic abuse, vice and criminality.

‘If they reside in habitations unfit for human beings, fever and pestilence will stalk forth and desolate the neighbourhood’

Dare wrote a comprehensive report every year of his tenure which described both the situation and the actions he undertook. It is a unique and important record of working-class life, and of his vocation as an early prototype social worker.

As well as practical help, he performed thousands of home visits each year to assess need, provide moral support and to comfort the dying. He was particularly concerned at the lack of educational opportunity and set up an additional Sunday School, a library and adult evening classes supported by chapel volunteers.

‘At times my door is almost daily thronged with applicants for advice or relief’

Not one to judge, he never made help dependant on chapel attendance, and took a broad-minded religious outlook. He rapidly came to the view that the laudable aim of fostering self-reliance and moral rectitude was futile without first correcting the underlying deprivation and illiteracy. Thus, he was an early adopter of the concepts of the ‘poverty cycle’ and ‘poverty of opportunity’ whereby people can become demoralised by poverty and circumstance and not by their own failings.

‘Whatever the poor are become, the nation, not to say the Government, is responsible for their condition’

Heritage displays in Chapel have been funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

In the nineteenth century Chapel members helped found the Mechanics Institute; the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society and the Leicestershire Archaeological Society.

In the twentieth century Joseph Fielding Johnson, a member of the congregation, was a major benefactor of University College, now the University of Leicester, and the main administrative block (which had been the old ‘County Lunatic Asylum’!) is now named after him.

Ministers to the congregation included a number of distinguished men. Revd. Charles Berry, together with the leading members of his congregation, played a major part in the movement for political reform in the town during the early nineteenth century.

The first seven mayors of the town following municipal reform in 1835 were members of the Chapel and as a result it became known locally as ‘The Mayor’s Nest’.

The graveyard was restored and converted to a garden in the late 20th century. If you wish to read about the fascinating and heartfelt gravestone epitaphs click here.

Today a number of members of the congregation are very active in public and political life.